This is the fifth chapter of a tutorial for building an AI agent for the racing game TORCS. In this chapter, we improve the steering angle of our AI Agent. We will use an heuristic approach to increase the radius of our car's path in turns, thus our speed as well.

Utility classes

First, let's introduce two classes to simplify our calculations in computing steering angles and specific distances.

The Vector Class

The first utility class Vector2D, represent a two dimensional vector. It

implement useful operations that can be applied to a vector such as: addition,

substraction, scalar multiplication and dot product. Additional implemented

functions are normalization, rotation around a center and computation of the length

of the vector.

Let's create a folder named linalg within our project. Within this folder create a file named vector2d.h. Implement the following listing in the created file.

#ifndef _VECTOR2D_

#define _VECTOR2D_

class Vector2D

{

public:

Vector2D() {}

Vector2D(const Vector2D &src) { this->x = src.x; this->y = src.y; }

Vector2D(float x, float y) { this->x = x; this->y = y; }

Vector2D& operator=(const Vector2D &src); // assignement

Vector2D operator+(const Vector2D &src) const; // addition

Vector2D operator-(void) const; // negation

Vector2D operator-(const Vector2D &src) const; // substraction

Vector2D operator*(const float scalar) const; // scalar mutliplication

float operator*(const Vector2D &src) const; // dot product

friend Vector2D operator*(const float scalar, const Vector2D &src);

float Length(void) const;

void Normalize(void);

float Distance(const Vector2D &point) const;

float Cosine(const Vector2D point1, const Vector2D point2) const;

Vector2D Rotate(const Vector2D ¢er, float arc) const;

float x;

float y;

};

/**

* Assignement. assigns the value of src to this

*/

inline Vector2D& Vector2D::operator=(const Vector2D &src)

{

x = src.x;

y = src.y;

return *this;

}

/**

* vector addition. Add *this to src.

*/

inline Vector2D Vector2D::operator+(const Vector2D &src) const

{

return Vector2D(x + src.x, y + src.y);

}

/**

* Negation of *this

*/

inline Vector2D Vector2D::operator-(void) const

{

return Vector2D(-x, -y);

}

/**

* vector substraction. compute *this - src.

*/

inline Vector2D Vector2D::operator-(const Vector2D &src) const

{

return Vector2D(x - src.x, y - src.y);

}

/**

* Multiply with a scalar

*/

inline Vector2D Vector2D::operator*(const float scalar) const

{

return Vector2D(scalar * x, scalar * y);

}

/**

* Dot Product

*/

inline float Vector2D::operator*(const Vector2D &src) const

{

return src.x * x + src.y * y;

}

/**

* Multiply a scalar with a vector

*/

inline Vector2D operator*(const float scalar, const Vector2D &src)

{

return Vector2D(scalar * src.x, scalar * src.y);

}

/**

* Length of the vector

*/

inline float Vector2D::Length(void) const

{

return sqrt(x * x + y * y);

}

/**

* Normalize the vector

*/

inline void Vector2D::Normalize(void)

{

float l = this->Length();

x /= l;

y /= l;

}

/**

* Distance between *this and point

*/

inline float Vector2D::Distance(const Vector2D &point) const

{

return sqrt(pow(point.x - x, 2) + pow(point.y - y, 2));

}

/**

* Cosine of the angle between vectors *this-point1 and *this-point2

*/

inline float Vector2D::Cosine(const Vector2D point1, const Vector2D point2) const

{

Vector2D l1 = point1 - *this;

Vector2D l2 = point2 - *this;

return (l1 * l2) / (l1.Length() * l2.Length());

}

/**

* Rotate the vector by 'arc' radians around the point 'center'

*/

inline Vector2D Vector2D::Rotate(const Vector2D ¢er, float arc) const

{

Vector2D d = *this - center;

float sina = sin(arc), cosa = cos(arc);

return center + Vector2D(d.x * cosa - d.y * sina,

d.x * sina + d.y * cosa);

}

#endif

The Straight Class

The second utiliy class Straight, represent some kind of

Euclidean vector.

We will use it to find intersection points among straights, and distances between

points and straights.

As you might see the Straight class contains two Vector2D. One hold a point

on the straight and the other the direction.

Let's create a file named straight.h within the linalg folder. Add the following code in the newly created file.

#ifndef _STRAIGHT_

#define _STRAIGHT_

#include "vector2d.h"

/**

* Represent an eucludean vector

*/

class Straight

{

public:

Straight() {}

Straight(float x, float y, float direction_x, float direction_y)

{

p.x = x;

p.y = y;

direction.x = direction_x;

direction.y = direction_y;

}

Straight(const Vector2D &point, const Vector2D &direction)

{

this->point = point;

this->direction = direction;

}

Vector2D Intersection(const Straight ) const;

float Distance(const Vector2D) const;

Vector2D point;

Vector2D direction;

};

/**

* Intersection point *this and s

*/

inline Vector2D Straight::Intersection(const Straight &s) const

{

float t = - (direction.x * (s.point.y - point.y) + direction.y * (point.x - s.point.x)) / (direction.x * s.direction.y - direction.y * s.direction.y);

return s.point + s.direction * t;

}

/**

* Distance of point s from straight *this

*/

inline float Straight::Distance(const Vector2D &s) const

{

Vector2D d1 = s - p;

Vector2D d3 = d1 - direction * d1 * direction;

return d3.Length();

}

#endif // _STRAIGHT_

Improving the steering

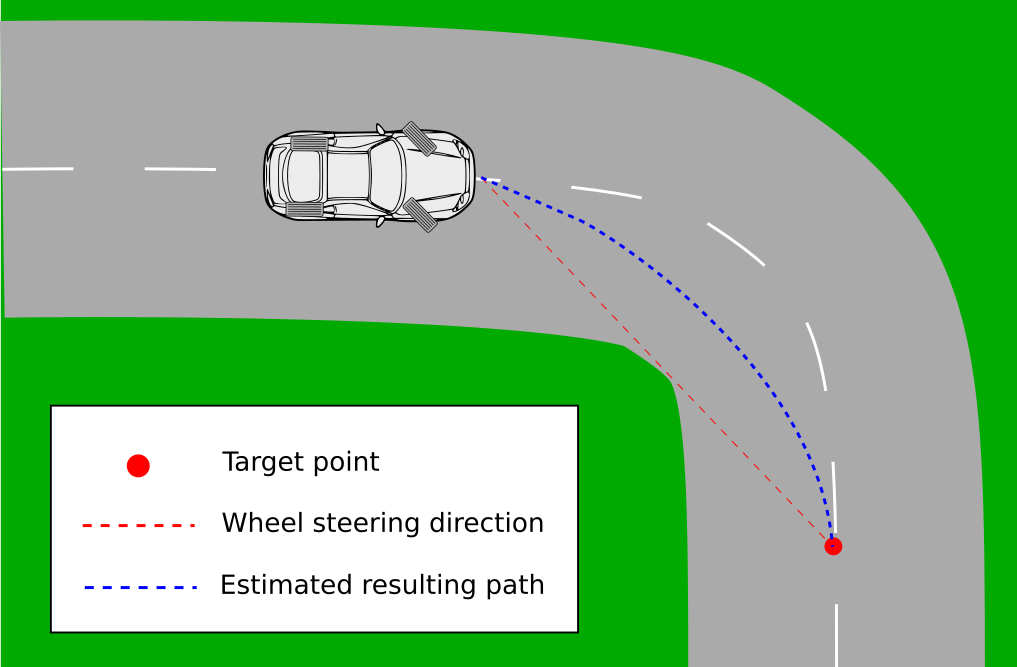

The new steering approach we will adopt can be explained as follow: from driving in the middle of the track, we designate a target point ahead of the car toward which we point the wheels. This result in greater turn radius of the car. The figure below give an idea of what goes on.

Although the overall path of the car will improve greatly, we have to note that we are still far away from a good trajectory, since we cannot take a turn with the biggest possible radius, starting and ending onthe middle of the track.

Finding the target point

To get the target point, we use the position of our car and the geometry of the

track. We first pick a distance at look_ahead meters from our car. We place a

point at the middle of the start of the track segment that is at the distance

we designated (Note in the code you will see below, the abbreviation for the

four vertices (points) of a track segment:TR_SL for start left coner, TR_SR for

start right, TR_EL for End Left and TR_ER for end right). If the point

is on a straight, the target point is formed by adding a scaled direction vector

otherwise, the target point is formed by applying a rotation to the point.

Here is the method to find the target point we add to carcontroller.cpp

/**

* Find a target point ahead of the car toward which the wheels will steer

*/

Vector2D CarController::GetTargetPoint()

{

tTrackSeg* segment = car->_trkPos.seg;

float look_ahead = LOOK_AHEAD_CONST + car->_speed_x * LOOK_AHEAD_FACTOR;

float length = DistanceFromCarToSegmentEnd();

while (length < look_ahead) {

segment = segment->next;

length += segment->length;

}

length = look_ahead - length + segment->length;

float target_x = (segment->vertex[TR_SL].x + segment->vertex[TR_SR].x)

/ 2.0;

float target_y = (segment->vertex[TR_SL].y + segment->vertex[TR_SR].y)

/ 2.0;

Vector2D target(target_x, target_y);

if ( segment->type == TR_STR) {

float direction_x = (segment->vertex[TR_EL].x - segment->vertex[TR_SL].x)

/ segment->length;

float direction_y = (segment->vertex[TR_EL].y - segment->vertex[TR_SL].y)

/ segment->length;

Vector2D direction(direction_x, direction_y);

return target + direction * length;

} else {

Vector2D center(segment->center.x, segment->center.y);

float arc = length / segment->radius;

float arcsign = (segment->type == TR_RGT) ? -1 : 1;

arc *= arcsign;

return target.Rotate(center, arc);

}

}

Heading toward the target point

Let's update the GetSteering() method to steer the wheels toward the target point

float CarController::GetSteering(float car_angle)

{

float target_angle;

Vector2D target = GetTargetPoint();

target_angle = atan2(target.y - car->_pos_Y, target.x - car->_pos_X)

- car->_yaw;

target_angle = remainder(target_angle, 2*PI);

return target_angle / car->_steerLock;

}

Finishing the Implementation

Let's define the new constants at the start of carcontroller.cpp

// ...

const float CarController::LOOK_AHEAD_CONST = 17.0; // [m]

const float CarController::LOOK_AHEAD_FACTOR = 0.33; // [1/s]

We also update carcontroller.h by including the Vector2D header, and

declaring the new class members.

// ...

#include "linalg/vector2d.h"

// ...

class CarController {

public:

// ...

static const float LOOK_AHEAD_CONST;

static const float LOOK_AHEAD_FACTOR;

// ...

private:

// ...

Vector2D GetTargetPoint();

// ...

};

Test Drive

[times]

Going Faster

We will modify CarController::GetAllowedSpeed(...), to pass short turns faster.

We consider short turns, turns with a small angle (see the figure below).

We will use a heuristic, which is just a an approach to reach an immediate goal

(going fast in short turns in our case), without worrying too much about

optimization, logic, or rationality.

In our heuristic approximation, we take the outside radius of the first segment

of the turn segment->radius + segment->width/2.0, and we divide it by the

square root of the angle (represented by arc) of the turn. Remember this is

a heuristic and don't try to make full sense of why it works. An interesting

advantage of this approach is the growing acceleration toward the end of a turn.

Here is the code of the new version of CarController::GetAllowedSpeed(...).

float CarController::GetAllowedSpeed(tTrackSeg* segment)

{

if (segment->type == TR_STR){

return FLT_MAX; // Max float number

} else {

float arc = 0.0;

tTrackSeg *seg = segment;

while(seg->type == segment->type && arc < PI/2.0){

arc += seg->arc;

seg = seg->next;

}

arc /= PI/2.0; // normalizing the turn angle

float mu = segment->surface->kFriction;

float r = (segment->radius + segment->width/2.0) / sqrt(arc);

return sqrt((mu * G * r) / (1.0 - MIN(1.0, r * CA * mu / full_car_mass)));

}

}

[Test drive and times]

Incidentally, this heuristic may lead the car to slightly go off track on some turns. We are about to fix that behavior.

Staying on the track

Now let's correct the unwanted behavior the car might have to slightly go off track due to the previously implemented heuristic, by introducing a marging around the middle of the track. We will readjust our acceleration depending whether we are in the inside or the outside of a turn. When we are far away form the middle at the outside of a turn, we set our acceleration to zero. In contrast when we are inside, we can accelerate further, because the centrifugal force pushes the car outside.

Let's add a method that implement that. A filter for our acceleration depending on our position on the track.

/**

* Acceleration filter according to the position on the track,

* to keep the car on the track.

*/

float CarController::FilterTrack(float acceleration)

{

tTrackSeg* seg = car->_trkPos.seg;

if (car->_speed_x < MAX_UNSTUCK_SPEED)

return acceleration;

if(seg->type == TR_STR){

float to_middle = fabs(car->_trkPos.toMiddle);

float safe_width = seg->width / WIDTH_DIV;

if (to_middle > safe_width)

return 0.0;

else

return acceleration;

} else {

float sign = (seg->type == TR_RGT) ? -1 : 1;

if (car->_trkPos.toMiddle * sign > 0.0){ // inside a turn

return acceleration;

} else {

float to_middle = fabs(car->_trkPos.toMiddle);

float safe_width = seg->width / WIDTH_DIV;

if (to_middle > safe_width)

return 0.0;

else

return acceleration;

}

}

}

We define the newly added constant at the top of carcontroller.cpp .

const float CarController::WIDTH_DIV = 4.0; // [-]

const float CarController::MAX_UNSTUCK_SPEED = 5.0; // [m/s]

WIDTH_DIV is a constant by which we divide the width of the track to get a safe width, and MAX_UNSTUCK_SPEED is a speed limit (it will also be useful in coming chapter).

We apply the filter at the end of the CarController::GetAcceleration() method,

before FilterTCL is applied.

float CarController::GetAcceleration()

{

// ...

acceleration = FilterTrack(acceleration);

acceleration = FilterTCL(acceleration);

return acceleration;

}

We can finally declare the new methods and constants in carcontroller.h.

class CarController {

public:

// ...

static const float WIDTH_DIV;

static const float MAX_UNSTUCK_SPEED;

private:

// ...

float FilterTrack(float acceleration);

// ...

};

[Test drive and Time]

Our AI agent start to be competitive right?

A quick discussion on trajectories

I can almost hear some of you saying: "...Bro, this ai robot trajectory kinda suck..."

So how can we manage to have great, near perfect trajectory ? How to find the optimal trajectory ? Like most people, I am still looking for that. Finding a perfect trajectory in three dimensions seems to be a NP problem. NP stands for non-deterministic polynomial time, and basically means that we are not sure if there is a correct (optimal) solution (in polynomial time), but if it does, we can make sure of it fairly quickly. A solution in 2D might also work since most track are pretty flat. I invite your to search the web for papers or other resources about the subject, but here we will discuss approach that are not perfect but might work well.

Heuristic Trajectories

Like you have seen heuristic means to find a trajectory with some reasonable ideas. So we improve our trajectory with adding this and that, improvement x causes problem y and so forth... The problem with heuristics is that they may work great on some tracks but also horribly fail on some other tracks or dislike certain features. You can build quite a good robot with this method, but there will be always problems with some track features.

Geometric Trajectories

We call a trajectory geometric when it just takes the track geometry into account, but doesn't consider the car setup and aerodynamics. Some examples include things like curvature linearization, cubic splines, clothoid, fitting arcs in the turns and other geometric stuff...

Soft Computing and Machine Learning Approaches

Soft computing denote techniques that yield (non-perfect) solutions to computationally hard tasks, including NP problems. Those approaches are tolerant of uncertainty and imprecisions.

Some of the techniques we can use for our AI agent include but are not limited to Fuzzy Logic that we can use for appreciating (braking, collision) distances, Evolutionary computing that we can combined with some geometric approches (e.g. to find splines points in a trajectory), we can also use Machine Learning techniques where we can find a lot of models we can creatively use to help us find a good racing trajectories.